Some context on axions.

For decades scientists noticed that quantum phenomena respect something called CP-symmetry, that is a really posh way to say “if you sub your particle with an antiparticle and invert its spatial coordinates, the laws of physics will stay the same”. So for example it doesn’t really matter if you have an electron at (1,1,1) or a positron at (-1,-1,-1), the effect is the same.

There are some exceptions (called CP violations) but for most part CP-symmetry is a real phenomenon. And one of those violations that could happen is when you’re dealing with quarks (the junk that protons and neutrons are composed of). And if something can happen, in quantum mechanics, it will happen. So why don’t CP violations happen?

Based on that, in 1977 Roberto Peccei and Helen Quinn predicted a new particle, that they named “axion” after some laundry detergent, as “it washed off the problem” (yup - scientists being silly with names, nothing new). That axion particle would be a really small particle, but with mass (unlike photons), and it compensates the predicted CP violation.

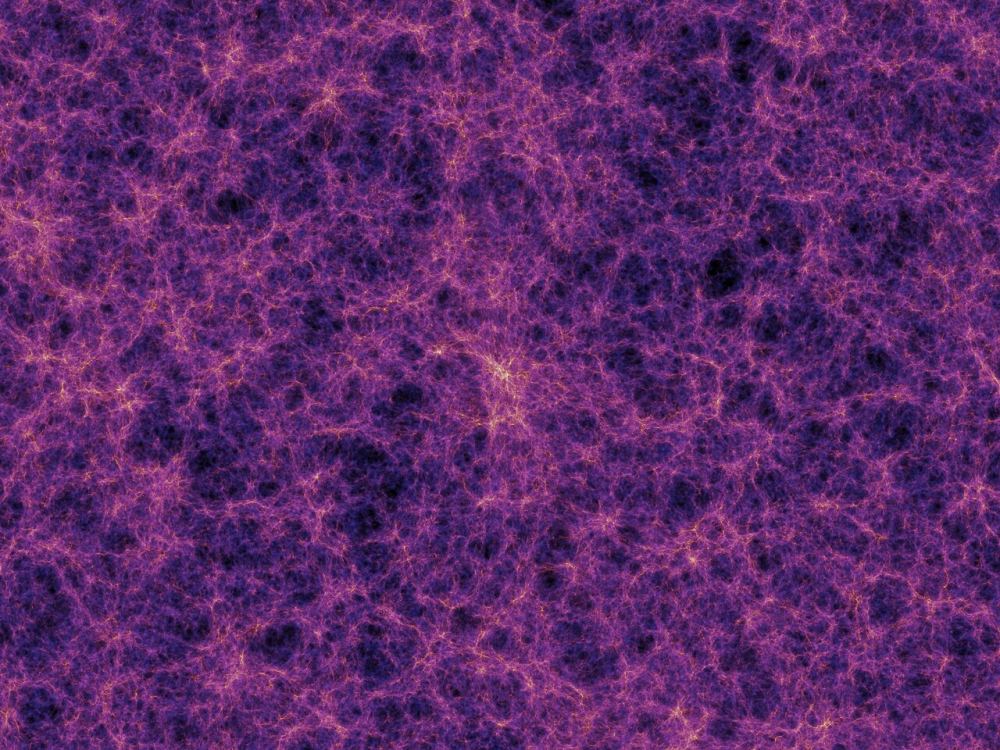

Now, to the link: apparently axions are a real thing, and they explain (at least partially) what dark matter is supposed to be.

We don’t know if axions are a real thing. This is still highly speculative.

Quantum mechanics explains these ultra-light particles as “fuzzy” because they exhibit wave-like behavior

How’s that different from any other particle? Aren’t they all waves in quantum fields?

I don’t know if this helps but starting at roughly 39:00 of this Fermilabs lecture the lecturer mentions that lighter the dark matter particle is more wave like it behaves and so you have to imagine like a “fluid” of waves that can be macroscopic.

Ok, I just gotta say that watching this type of talk here, puts my mind at rest that the Fediverse is going to be alright. That we are in the right place.

We got the smart people from Reddit

We are the smart people from Reddit. Even if we don’t know everything, we know which way the wind is blowing.

Speak for yourselves, I’m an idiot